PUBLISHED

February 08, 2026

KARACHI:

Has your mobile internet usage been slower than molasses? Over the past year, many users across Pakistan have witnessed the same frustration. Videos that once loaded instantly now pause for a second too long. Calls freeze mid-sentence. A simple page refresh steals enough of your time to annoy? It is not a dramatic collapse, but a gradual slowing – the kind that slips into daily routines almost unnoticed, until one day it becomes impossible to ignore.

In Karachi, peak hours now carry a familiar frustration. Late evenings in Defence and Clifton, lunch breaks in Saddar, and morning traffic around Shahrah-e-Faisal often bring visible drops in speed. Lahore’s Gulberg and Johar Town, Islamabad’s Blue Area and G-10 report similar patterns. Signal bars may still be full, but the experience feels thinner, stretched.

Part of this shift has unfolded quietly since the pandemic. Covid did more than temporarily push work and education online; it permanently altered how the internet is used. Ride-hailing apps became daily tools. Small businesses moved orders and customer engagement onto messaging platforms. Payments turned digital. Content creation, livestreaming, and short-video apps began consuming steady streams of data. Even outside major cities, smartphones evolved into workstations, classrooms, and shopfronts rolled into one.

For freelancers, the slowdown has practical consequences. Uploads stall. Video calls drop for seconds at a time. Cloud-based tools become unreliable. Students attending online classes experience buffering at the wrong moment. Small businesses dependent on social media find themselves retrying actions that once worked seamlessly.

The pressure is no longer confined to urban centres. In smaller towns and rural areas, mobile internet has become the primary gateway to services, markets, and information. What was once a supporting tool is now an essential utility, expected to work constantly.

Among users, a common refrain has begun to surface. The internet, many say, used to be better. Not faster in the headline sense, but more reliable, less fragile under load. The question that follows is simple: why does a network that once seemed adequate now feel strained?

Why 5G alone won’t fix Pakistan’s internet

As frustration has grown, a familiar solution has taken hold in public conversation. Launch 5G. In political statements, advertising language, and everyday discussion, the next generation of mobile technology is often treated as a switch that will make the internet faster, smoother, and future-ready.

The assumption is easy to understand. Each previous upgrade brought visible gains. 3G enabled basic browsing. 4G made video practical. In that progression, 5G is imagined as the next leap forward, a technological cure for buffering screens and dropped calls.

But this framing is incomplete. It confuses technology with capacity. A new generation does not automatically create space; it only determines how efficiently the available space is used. If the underlying network is already crowded, introducing a new standard does little to ease the pressure.

Mobile internet runs on finite airwaves. Every video streamed, call made, ride booked, or payment processed draws from the same shared pool. When that pool is stretched thin, the result is not failure but degradation. Speeds dip. Latency rises. Reliability weakens, particularly during peak hours. A newer technology may handle data more efficiently, but it cannot create room where none exists.

This is why the promise of 5G often sounds larger than its immediate impact. In many countries, its most transformative uses lie beyond everyday browsing, in specialised applications that require dense infrastructure, compatible devices, and long investment cycles. For most users relying on smartphones for work, study, and communication, the more urgent need is simpler: an internet connection that works consistently.

As the debate around Pakistan’s digital future intensifies, industry and regulatory voices increasingly argue that the problem is not the absence of a new generation, but the exhaustion of the old one.

To understand why mobile internet slows down, it helps to understand what “spectrum” actually is. In simple terms, spectrum refers to the invisible radio frequencies that carry data between a mobile phone and a nearby tower. Unlike fibre cables, which can be expanded physically, the spectrum is finite. Only a limited amount exists, and it must be shared by everyone using the network in a given area.

When relatively few users are connected, the experience feels smooth. As more people come online at the same time, that shared space becomes crowded. The network does not stop working; it divides capacity among users, slowing each individual connection. This is why internet quality dips during peak hours and in dense urban centres. The issue is not access alone, but whether there is enough spectrum to carry the volume of data modern smartphone use now demands.

Operator reality: Pakistan has run out of road

For those operating Pakistan’s mobile networks, the recent slowdown is neither sudden nor unexpected. It is, as one senior executive at one of the country’s largest mobile network operators explained, the cumulative result of a system that has been stretched far beyond its original design.

“Mobile spectrum is like the width of a road,” he said. “If the number of cars keeps increasing on that road, traffic will slow down. You cannot defy the laws of physics. If you want to move more cars smoothly, you have to widen the road. What we have done in Pakistan is add more and more cars, without widening the road.”

The executive’s analogy captures what operators describe as the core structural problem. While mobile data consumption has risen sharply over the past decade, the amount of spectrum available to carry that traffic has not expanded at the same pace. As a result, networks are forced to distribute limited capacity among a growing number of users, particularly in dense urban centres.

According to him, this explains why many users feel that 4G is no longer delivering what it once did. “There is nothing wrong with 4G as a technology,” he said. “What has changed is the load. When thousands of people in the same area are all streaming video, joining calls, booking rides, and uploading content at the same time, the network has no option but to divide time and bandwidth between them. Everyone stays connected, but the experience slows down.”

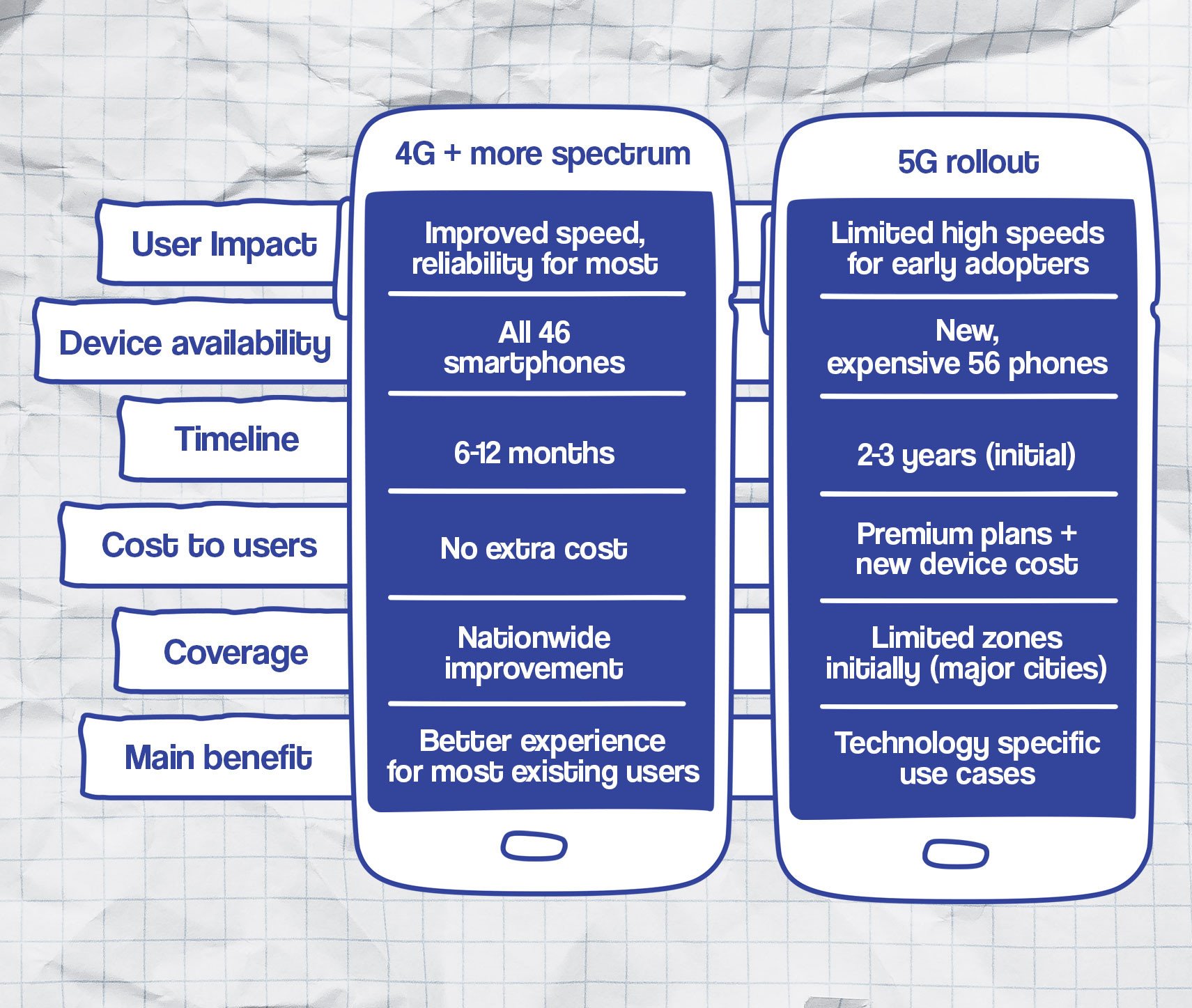

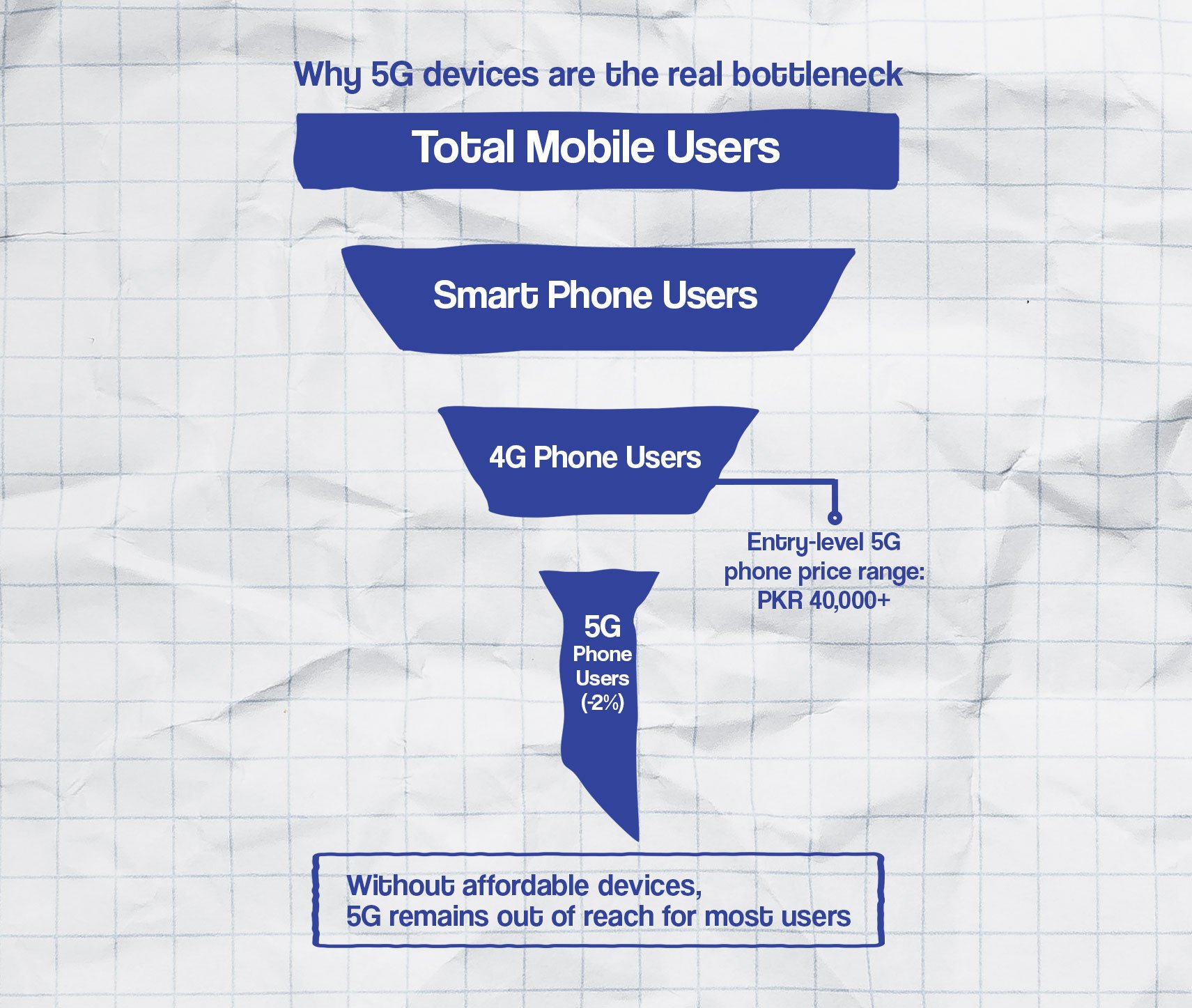

From the industry’s perspective, this is why simply launching 5G is not a guaranteed fix. Without additional spectrum and broad device adoption, a rapid rollout risks benefiting only a narrow segment of users. “If we launch 5G tomorrow without solving the ecosystem issues, it will work for maybe two or three percent of people,” he said. “That turns it into a premium product, not a national solution.”

The financial reality reinforces that caution. Rolling out next-generation networks requires sustained capital investment, often with payback periods stretching seven to ten years. In a market like Pakistan, where purchasing power is limited and smartphones capable of fully using 5G remain expensive, returns depend heavily on affordability. “If people cannot afford the devices, they will not upgrade,” the executive said. “And if users do not upgrade, operators will hesitate to invest.”

This creates a familiar stalemate. Operators are reluctant to deploy infrastructure without users. Users are reluctant to buy devices without coverage. Breaking that cycle, he argued, requires addressing capacity and affordability first. Mechanisms such as handset financing and instalment plans could accelerate adoption, but without them, progress will be uneven.

For the industry, the immediate priority is therefore pragmatic rather than symbolic. Expand the spectrum. Reduce congestion. Restore reliability to existing networks. Only then, the executive suggested, can the transition to 5G be gradual, inclusive, and economically sustainable. “The real test,” he said, “is not whether we can say 5G has launched, but whether the internet actually works better for the people who depend on it every day.”

On the core diagnosis, there is little disagreement between industry and regulator. Pakistan’s mobile networks are under strain because demand has grown faster than the capacity available to carry it. Regulators argue the coming spectrum auction is designed to widen that capacity deliberately, restoring balance to existing networks while preparing for future services, without turning spectrum into a one-off revenue exercise or forcing a premature technological leap.

PTA explains the spectrum problem, in numbers

From the regulator’s perspective, the strain visible on mobile networks is rooted in a simple arithmetic problem. Pakistan, officials say, has been trying to serve a rapidly expanding digital population with a limited and largely unchanged pool of mobile spectrum.

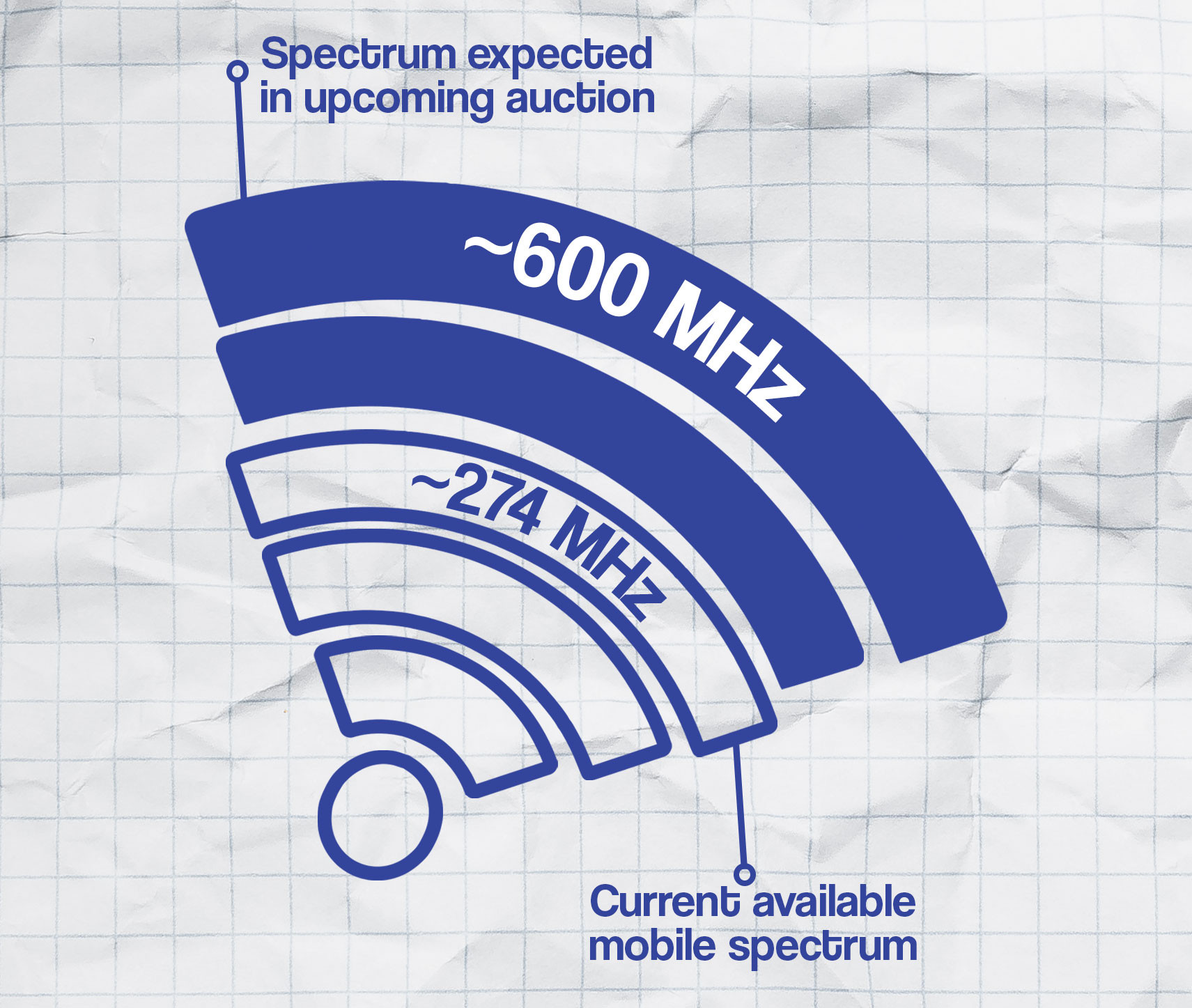

“Today, the total spectrum that has been allocated to all mobile operators in Pakistan for broadband services is about 274 megahertz,” Brigadier (R) Amer Shahzad, Director General Licensing at the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority, told The Express Tribune. “This spectrum is spread across four main bands, 850, 900, 1800 and 2100 megahertz, and it is this shared resource that carries all mobile data traffic.”

According to Shahzad, congestion is best understood as a function of how spectrum is shared rather than how much infrastructure exists on the ground. “When a person is connected from a tower to a smartphone, voice uses a very small channel,” he explained. “But broadband applications like video streaming require several megabits per second. When many users are active at the same time, the network has to divide time slots between them. Everyone remains connected, but each user gets a smaller share, and the experience slows down.”

What changed after the pandemic, he noted, was not the technology but the intensity and simultaneity of use. Activities that were once spread across time became constant and overlapping. “The demand pattern shifted,” Shahzad said. “Usage became continuous rather than occasional, while the available spectrum stayed the same.” That mismatch, he added, is what turned latent capacity limits into a visible quality-of-service issue.

It was this mismatch, he said, that prompted a reassessment of spectrum availability and long-term needs. “We conducted a detailed exercise to identify which existing bands were available and which bands had a mature ecosystem globally for both 4G and 5G,” he said. “Based on that, we decided to bring a much larger amount of spectrum to the market.”

The upcoming auction will release approximately 600 megahertz of additional spectrum, more than double what is currently in use. Shahzad described this as a deliberate shift in approach. “The objective is not just to introduce a new technology, but to address congestion in existing networks while also preparing for future demand,” he said.

A key feature of the auction design is technology neutrality. Rather than prescribing how each band must be used, PTA will allow operators to decide how best to deploy the spectrum they acquire. “The choice will be with the operator,” Shahzad said. “They can use a band for 4G or 5G depending on their technical plan and business case. Different bands have different ecosystems, and operators will naturally deploy 5G where the ecosystem exists and demand justifies it.”

This flexibility, he argued, is central to ensuring that additional spectrum translates into real-world improvements. “Our goal is simultaneous improvement,” Shahzad said. “Relief for 4G where congestion exists, and a gradual, demand-driven rollout of 5G in areas where it makes sense.”

In regulatory terms, the auction is intended to reset the capacity equation. By expanding the available spectrum pool and removing rigid technology constraints, PTA hopes to give operators the room they need to stabilise existing services while building toward the next phase of mobile connectivity. Whether that promise translates into a better experience for users, Shahzad acknowledged, will depend on how effectively that new capacity is deployed, a question the regulator says it plans to monitor closely in the years ahead.

4G first, 5G gradually

One of the most persistent misconceptions around Pakistan’s digital future is that improvement depends almost entirely on how quickly 5G is launched. PTA officials argue that this framing misses the regulator’s central objective, which is not speed for its own sake, but a staged improvement in everyday internet quality across the country.

“Our approach is very clear,” said Shahzad. “Since 4G is already running nationwide, it will continue to carry the bulk of mobile traffic. The first responsibility is to improve 4G quality everywhere, while 5G is introduced gradually where demand, infrastructure, and devices justify it.”

To that end, PTA has revised its quality-of-service benchmarks significantly. Under the new licensing conditions, the minimum average speed for 4G services will rise from the existing 4 Mbps to 20 Mbps nationwide in the initial phase. “This is not limited to major cities,” Shahzad said. “Nationwide means nationwide. Urban and rural areas are both included.”

The benchmarks then escalate over time. “After the next phase, operators will be required to reach 35 Mbps, and ultimately 50 Mbps for 4G,” he explained. “These are time-bound milestones written into the licence conditions, not aspirational targets.”

For 5G, the thresholds begin higher. “We are starting 5G at a minimum of 50 Mbps,” Shahzad said. “Over time, this will move toward 100 Mbps. The idea is that if 5G is offered, it must offer a clearly superior experience, not marginal improvement.”

Deployment, however, will follow demand rather than symbolism. PTA expects operators to prioritise dense urban centres and high-usage corridors first, while avoiding unnecessary investment in areas where advanced services would see little uptake. “It would not make sense to deploy high-end 5G equipment in locations where there are very few compatible devices,” Shahzad said. “That does not mean rural areas are ignored, but that the technology is matched to actual needs.”

To ensure progress is not delayed, PTA has set minimum rollout obligations. Each operator will be required to deploy at least 1,000 new sites annually, more than double previous benchmarks. Compliance will not be taken on trust alone. “We conduct nationwide surveys,” Shahzad said. “If quality standards are not met within the defined timelines, show-cause notices are issued, and operators are required to upgrade.”

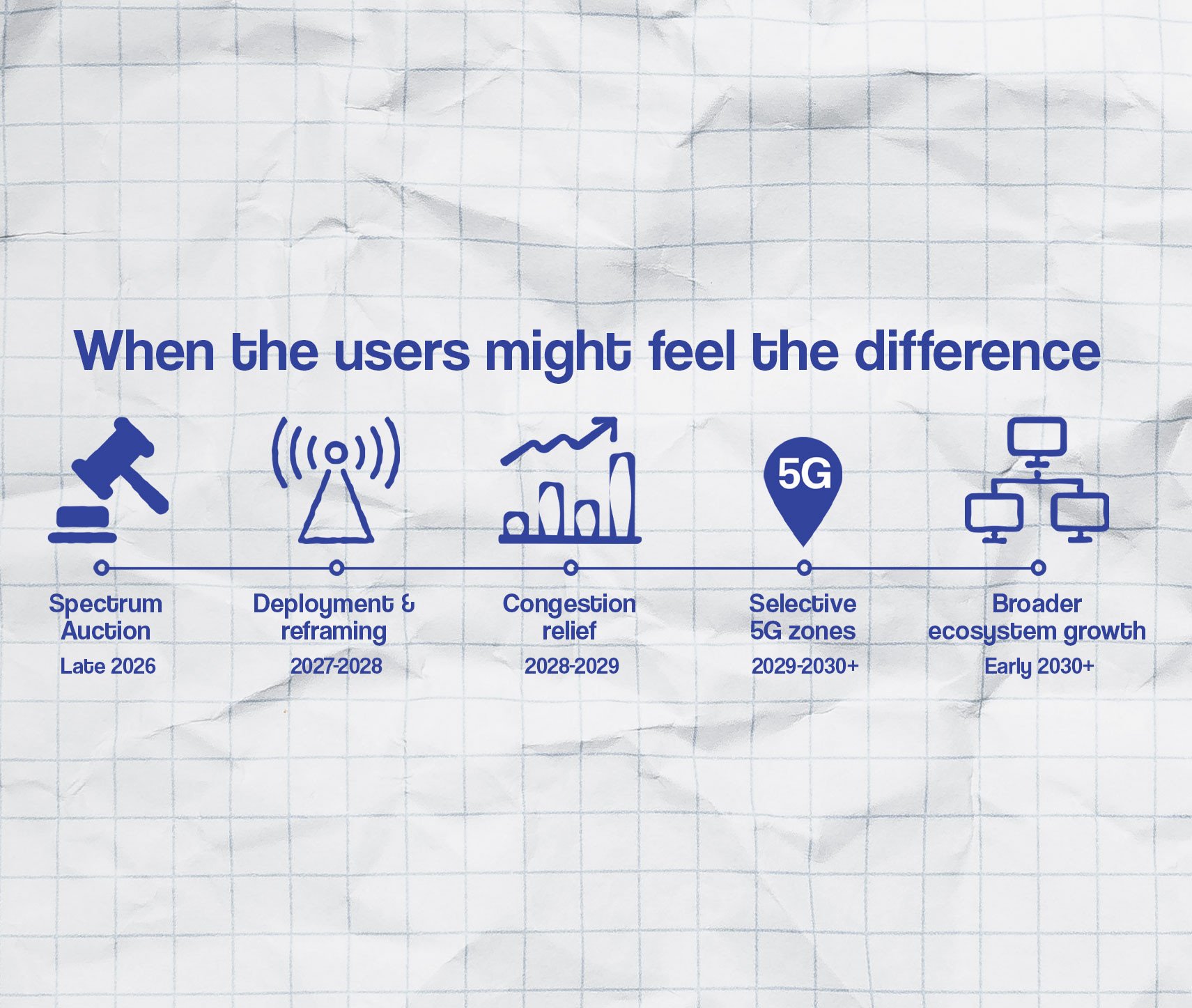

In practical terms, PTA estimates that users should begin to notice improvements within months of the auction. Equipment orders, site upgrades, and multiband deployments are expected to follow quickly. “We are not talking about overnight change,” Shahzad said. “But within six months of spectrum allocation, services will begin to improve.”

The sequencing, he stressed, is deliberate. “The goal is not to announce 5G,” he said. “The goal is to make the internet work better, first through stronger 4G, and then through a sustainable transition to 5G.”

Where regulator and operators agree

Despite frequent tension around telecom policy, there is notable convergence between regulators and industry on the core diagnosis of Pakistan’s internet problem. On this point, both sides appear aligned: the constraint is capacity, not technology.

Both acknowledge that spectrum scarcity has become structural. Mobile networks are carrying far more data than they were originally designed to handle, particularly in dense urban areas where usage is constant and overlapping. The result is congestion that degrades quality even when coverage remains intact.

There is also agreement that improving 4G matters more immediately than accelerating a nationwide 5G launch. While 5G is seen as inevitable, neither side views it as a short-term fix for everyday connectivity. Device affordability reinforces that caution. Advanced networks offer limited value if users cannot access them, and both regulators and operators accept that adoption must emerge gradually.

Finally, both sides stress the importance of investment certainty. Expanding networks requires long-term capital planning. “This is not a one-year or two-year investment,” a senior industry executive said. PTA officials echo that view, arguing that predictable rules and phased obligations are essential to turning new spectrum into lasting improvements.

Where differences remain, they lie largely in sequencing and execution, not in how the problem itself is understood.

The unresolved tension

Despite broad agreement on the diagnosis and direction, significant questions remain about how quickly policy intent can translate into everyday improvements. At the centre of that uncertainty lies a familiar challenge: devices, affordability, and the pace of execution.

From a regulatory perspective, there is confidence that the ecosystem will respond. Officials argue that once spectrum is released and networks begin upgrading, handset manufacturers and vendors will adapt. As coverage expands, prices are expected to fall, chipsets to diversify, and affordable models to enter the market. In this view, demand and supply will gradually align, just as they did during earlier technology transitions.

Operators are more cautious. While acknowledging that device prices will eventually come down, industry executives warn that the timeline matters. If affordable 5G handsets do not arrive quickly enough, adoption will remain limited to a narrow segment of users. That, in turn, weakens the business case for aggressive rollout. The concern is not about whether affordability will improve, but whether it will do so at a pace that justifies sustained investment.

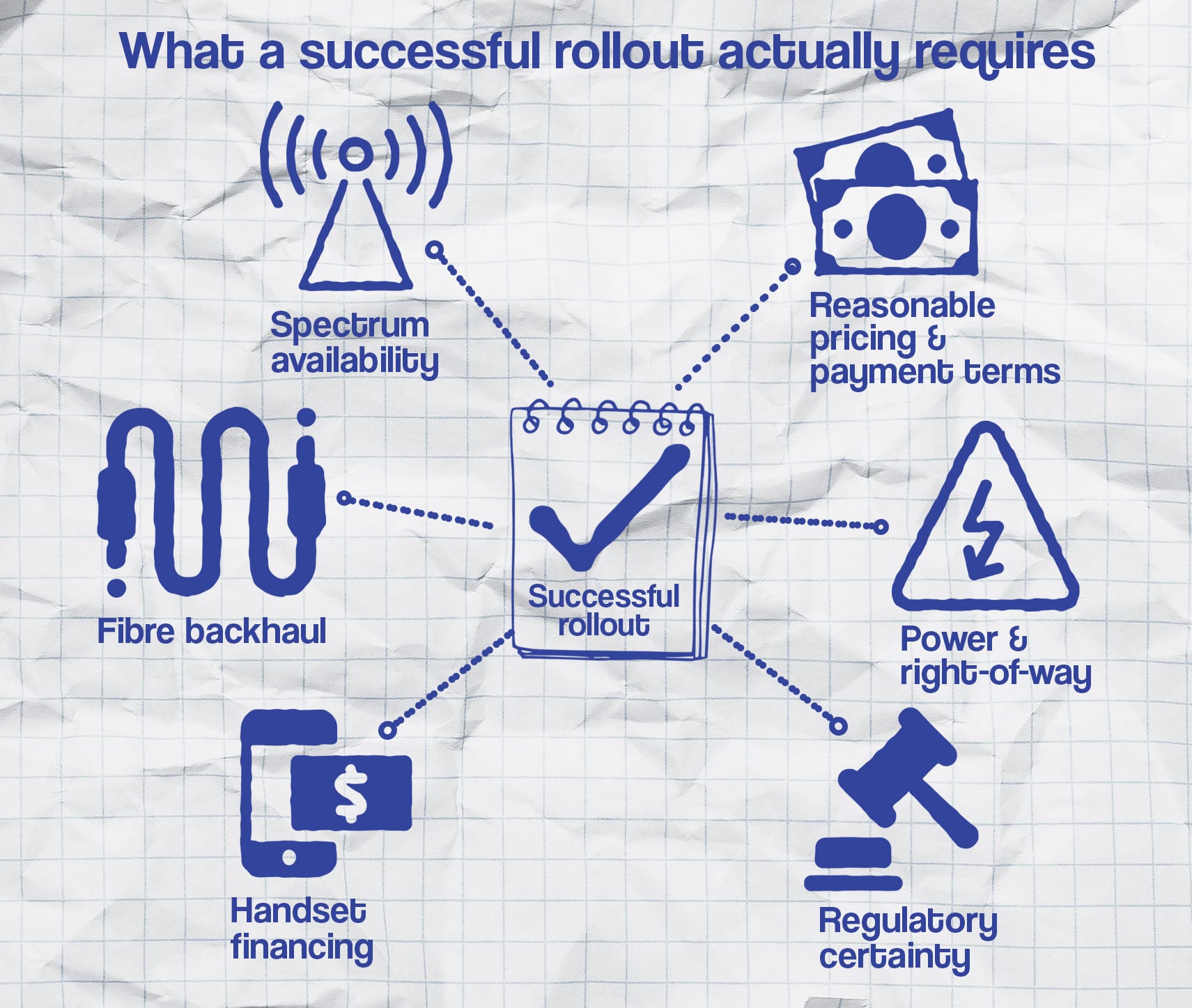

Execution poses another test. PTA’s rollout obligations are ambitious, requiring operators to deploy thousands of new sites and upgrade existing infrastructure within defined timelines. On paper, the targets are clear. In practice, they depend on factors beyond policy documents: equipment availability, supply chains, power costs, right-of-way approvals, and the capacity to build at scale. Any delays in one part of that chain can slow progress across the system.

Rural impact remains a particularly sensitive question. While regulators stress that nationwide benchmarks apply to both urban and rural areas, operators point out that upgrades are often demand-driven. Advanced services tend to appear first where usage and revenue potential are highest. The risk is not exclusion, but lag, a gap between policy guarantees and the speed at which improvements reach less dense regions.

Underlying all of this is a deeper uncertainty about reliance on market forces alone. Financing mechanisms, instalment models, and supportive policies could accelerate adoption, but their implementation remains uneven. Until those pieces fall into place, Pakistan’s transition risks becoming incremental rather than transformative.

What success will actually look like

With the auction now scheduled for March 10, 2026, expectations around what comes next are already rising. PTA officials are careful to temper those expectations. The changes set in motion by the auction, they argue, are significant, but they are not instantaneous.

Once spectrum is allocated, operators will still need time to place equipment orders, import hardware, upgrade sites, and integrate new bands into existing networks. PTA estimates that visible improvements should begin within six months of the auction, as new equipment comes online and congestion eases in high-traffic areas. These gains, however, are expected to be gradual rather than dramatic.

“This is not an overnight switch,” said PTA Director Shahzad. “But once a spectrum is assigned, operators already know where congestion exists. They will move quickly, because this is a competitive market.”

That competitive pressure is central to the regulator’s expectations. With multiple operators chasing the same users, any early improvement by one network is likely to force others to respond. In that sense, the auction is designed to trigger a cycle of investment rather than a single upgrade event.

To support that investment, PTA has also adjusted the financial structure of the auction. Unlike previous sales, the government is not demanding upfront payment. Operators will receive a one-year moratorium, followed by a phased payment schedule spread over several years. The intent, Shahzad said, is to prioritise infrastructure over immediate revenue.

“The objective this time is to allow operators to invest aggressively in the network,” he said. “If all the money is taken at the start, there is little left for rollout.”

According to PTA, the auction design and payment terms were shaped with the help of an international consultant, who studied spectrum sales and rollout models across dozens of markets. The aim was to strike a balance between spectrum pricing, rollout obligations, and long-term economic impact, shifting the focus from short-term receipts to sustained connectivity gains.

That framing matters because what is at stake extends beyond mobile speeds. Connectivity now underpins freelance work, digital payments, education, logistics, health services, and small business growth. In that context, spectrum is not merely a technical resource but an enabling layer for economic activity.

Whether the auction succeeds will ultimately be judged not by how quickly 5G appears on marketing banners, but by whether everyday internet use becomes more reliable. Faster uploads during peak hours. Fewer dropped connections. Smoother video calls. The absence of the small frustrations that have quietly become normal.

In the end, better internet is not a headline or a launch event. It is an experience, one that most users will only notice when it stops getting in the way of their work, their studies, and their lives.